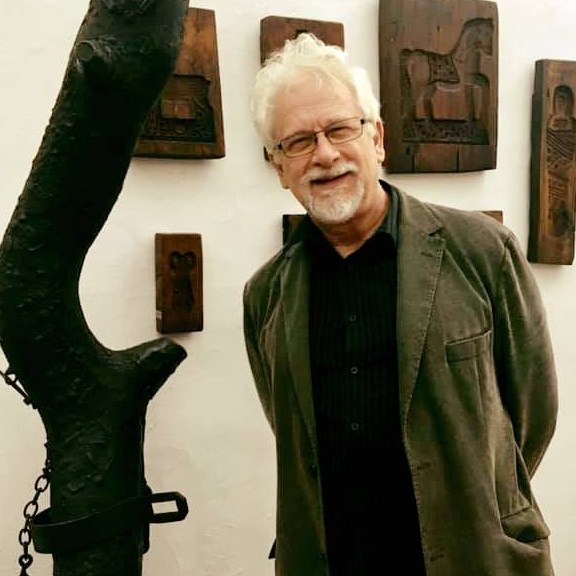

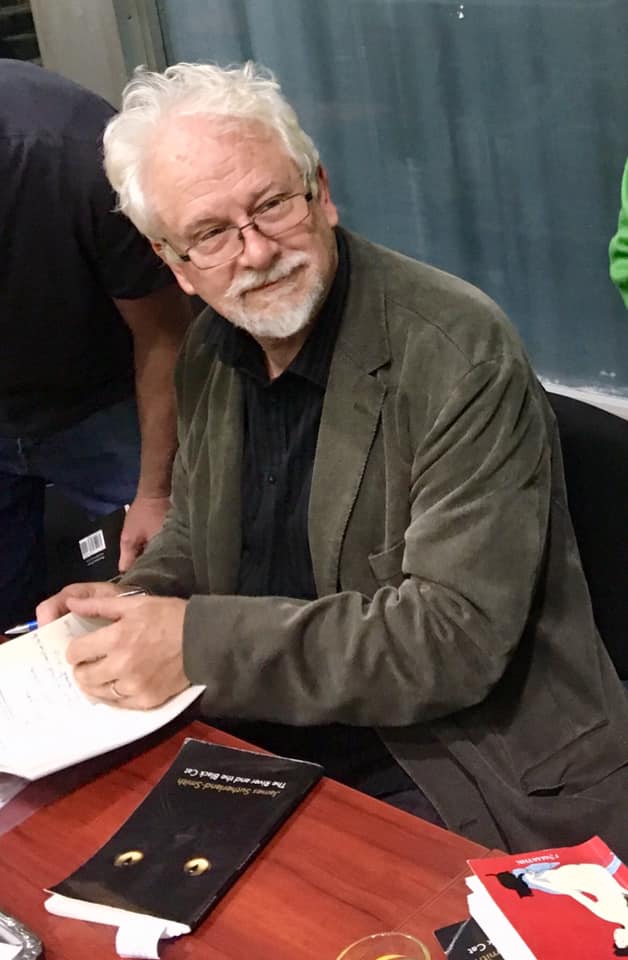

JAMES SUTHERLAND-SMITH was born in Scotland, but lives in Slovakia. He has published seven collections of his own poetry, the most recent being “The River and the Black Cat” published by Shearsman Books in 2018. He also translates poetry from Slovak and Serbian for which he has received the Slovak Hviezdoslav Prize and the Serbian Zlatko Krasni Prize.

His most recent translation is from the poetry of Mila Haugová, Eternal Traffic, published in Britain by Arc Publications.

A SNAIL IN ISTANBUL

The sultan of moisture creeps

On a flagstone shadowed by nettles.

He carries his turban on his back

And shows his tentacles, a scholar

Bareheaded out of the mosque.

No doubt his hidden mouth is prim

Though his tongue, rough with hunger

Not prayer, will rasp on greenery:

One foot, one lung, one kidney,

One gonad, mostly male, feminine

Only in summer in a place

The Turkish guidebook labels

The Convent of the Whirling Dervishes.

In the octagon of the dance hall,

On a balcony wall overlooking

The dancing floor is a photograph

Of abandoned holy men, a cluster

Of white frowns with unkempt beards

Like snails stuck to a glossy leaf.

They lingered after Sheikh Galib

The last, great formal poet,

Years after Halit Efendi

Whose body is in a tomb outside.

His head is buried elsewhere.

Their pens and mechanical verses

Are displayed, nibbled by neglect.

On the path the devotee of stealth

Has almost reached the nettles.

His spiral of shell and viscera,

His delicacy, will not be scourged

By the stinging hairs on the stems.

Far above him the curator

Picks tobacco from a lower lip

Before he brushes down the graves

Tilted by subsidence so they seem

Almost imperceptibly to make

A gesture in the dance. Their headstones

Are grey, bearded with inscriptions,

Crested with marble turbans.

PRICKLY PEARS AND ORANGES

Prickly pears are a rabble of headless men

Whose limbs have yellow flowers drooping

Like cotton gloves with empty fingers.

Their fruit first appears livid as a rash

Then matures in carbuncular clusters.

Harvested they are pruned back to thickets

High and close enough to deter small boys

From banditry in the formal orange groves

Where young goats play king-of-the-castle.

Hacked, burnt, then ploughed in deep by claimants

To a promised land they resurrect

In a straggle of spiky ovals.

They re-assert boundaries of alfalfa,

Of villages deliberately de-named,

Settled over, portioned in another tongue.

Rooted out again they still spring up

From the hidden stubbornness of seed,

A vegetable remembrance

Long after incinerated title deeds,

Long after the requisition document

Whose lie is “for reasons of security”,

Long after the exodus of smallholders;

Bemused old men on donkeys dreaming,

As they rode away, of prickly pears

And oranges – circles of ripeness,

Globes of paradise beneath glossy leaves –

Which could be quartered easily

For the satisfaction of the palate.

Now the memory of their taste provides

Bitterness for the politics of loss.

It is difficult to eat the prickly pear.

You have to soak it overnight

Otherwise the brittle spines break off

Then splinter as they lodge beneath your skin.

But if you manage to survive you open

A sweetness whose softened rind parts at your touch.

A WORLD OF MUSIC

The music man with his cap on the ground

And his toothless carnivorous stare

Makes the world succulent with his repertoire

Though his is not the only sound.

There’s a horrible scraping from the main street,

A dawdle of Bach and Mendelssohn from the square.

For it’s Spring and the beggars come out from their lair

To display their stumps and misshapen feet

For money, some kneeling in postures of abasement

Making no sound whatever though they pucker their lips

And their hands twitch right down to their fingertips

As if they played an invisible instrument.

You walk between them fiddle case in hand

Knowing that it only takes one false note

For you to tumble down the scale and share their fate.

From harmony to cacophony: you’ve found

It needs a semi-tonal, a micro-tonal slip.

So you walk between disaster and disaster,

The dread of error, of your music master,

Lathering you about the head with his cap.

VISION

It is near winter in Celestial County,

flat clouds over mountains ribbed with early snow,

meadows cropped by sheep to a fuzz of brown roots,

the river still flowing, a moving mirror.

I have scrambled up through beech and tall pine

from my cabin to a sparser fantasy,

an avenue of aspen, clusters of birch

behind which could be shapes of beasts I can’t name.

I wish to see the angels who ride up here

on their grey stallions, high in the saddle

yet easy at a gallop, Wyoming style,

their yelps neither anathema nor blessing.

But the space is empty, the distances meek.

Above me I watch a hawk fold its wings and drop.

SIBERIAN IRISES

All day there’s been the tremulous

impersonal rattle of a whitethroat’s song

as it delves for insects in the valleys

and ridges of the apricot’s bark.

A wasp with a red abdomen sneers

over the winter garden’s glass roof

above which a ghost of gold and sky-blue

shimmers behind gauzy net curtains.

And so our vision hesitates down

to the irises whose indigo

has a recollection of red

and something of the dark between the stars.

In forty-eight hours they’ve altered

from black dogmatic spearheads to the curve

and countercurve of petals round a tongue,

pistils feathered with stamens, mild milky white.

Tomorrow they’ll have withered to twists

of ancient carbon paper, all while the moon

moves from incompletion through perfect form

to a Roman coin clipped on one side,

all while you change from apparition

at an upstairs window through flesh and blood

to shrivelling scorn as the whitethroat sings

my fortune like dice clattering in a cup.